Emeritus Life explores the careers and post-retirement life of Emeritus Faculty from the Department of English. In our fourth feature, we catch up with Dr. Ellen Pollak, who retired in 2012.

Dr. Ellen Pollak, Emeritus Professor of English

Dr. Ellen Pollak, Emeritus Professor of English

What years did you teach in the English Department?

I taught in the English Department for 23 years–from 1989, when I joined the department as Associate Professor, until my retirement in May of 2012. Previously, I had been Assistant Professor of English at the University of Pennsylvania (1980-88) and I subsequently spent a year teaching and doing research on a Mellon Fellowship at Harvard. But the MSU English Department was my intellectual and academic home for the vast majority of my 32-year career.

What are some memorable moments from your English classrooms?

After a decade of retirement, specific moments from the classroom are hard to resurrect, but one—from way back in 1990–has stayed with me all this time. Having previously taught at elite institutions with a great deal of homogeneity, I was discovering the unique value of the MSU classroom, where conversations occur among an enriching variety of ages and lived experiences. I was teaching a graduate course called “Feminist Literary Criticism: 1970 to the Present”–a history of feminist criticism since its emergence as a distinct academic practice in the U.S., beginning in 1970 with the publication of Kate Millet’s groundbreaking work Sexual Politics, the first text on our syllabus. Though listed at the masters level, the course was open to qualified Honors College undergraduates with instructor approval.

At the first class meeting, I asked students to introduce themselves and talk about why they had chosen to take the course; what previous experience, if any, had they had with feminist criticism–or simply with feminism–and how had it touched their lives? I began the process by sharing that I had started graduate school at Columbia in 1970– an exhilarating time, as Sexual Politics (which was based on Millet’s recently defended Columbia dissertation) had just been released by Doubleday and was causing quite a stir both in the academy and at large. We then proceeded around the room: some students confessed that they had enrolled in the course primarily to fulfill a requirement; a few said they’d had no previous exposure to feminist criticism, but were curious; others reported modest exposure in high school or college and a desire to learn more. Most memorably, an older graduate student in English Education reported that in 1970 she’d been home caring for her first child; and an English major from the Honors College closed the circle by declaring himself a feminist with an avid interest in the field and announced that, by the way, 1970 was the year when he was born.

Multiple histories converged around a single year for individuals of diverse ages, backgrounds and experiences who had come together to study a common set of texts. 1970: the birth of an academic movement; the beginning of a graduate career; the publication of one of the field’s foundational texts; the birth of two babies–one whose mother resumed her formal education and began a graduate career in mid-life, and one who came of age as a feminist during the same two decades when academic feminism itself matured and began to filter into secondary and college curricula. A perfect beginning for productive exchange.

What were your favorite courses and texts to teach and why?

I loved teaching courses on the early development of the British novel. Given the popularity of the novel as the reigning modern literary genre, it was always interesting to me to be able to defamiliarize the form for students by examining it in the process of formation. I enjoyed introducing students to the ways in which eighteenth-century male writers whose work would come to constitute the British novelistic canon (e.g., Richardson and Fielding) capitalized on print markets and narrative strategies established by earlier, mostly female, writers of popular fiction (e.g., Behn, Manley, Haywood) and then, rather than acknowledging debts to their female predecessors, dismissed women writers as licentious hacks in order to establish their own efforts on more elevated moral and cultural ground. I found that novel-loving students mainly familiar with Victorian and post-Victorian fiction were often amazed by the ironic and sometimes frankly metafictional aspects of eighteenth-century novels, and that most were even more astonished by the bawdy, irreverent, and deeply subversive work of early women writers. I never tired of unsettling their expectations while sharing the pleasures of these works with them.

How do you hope your scholarship and mentoring has impacted your field? What do you hope early career scholars in your field take away from your research?

Supporting graduate students and younger colleagues in the department and in my field has always been important to me, so I hope my efforts have reaped benefits for others along the way. More concretely, I am proud to have helped establish the English Graduate Program’s “Feminisms, Genders, Sexualities” Emphasis Area in the mid-2000s and to have worked with Zarena Aslami, Sandra Logan, Lynn Makau, Ellen McCallum and Jennifer Williams to establish and obtain funding for the Feminist Theory and Literature Working Group (FLATwg) in 2007. FLATwg developed courses, organized symposia, built a working archive of feminist texts, and was the crucible for the department’s current FSG Cross-Field Area of Inquiry. I’m happy to see those efforts carry on as a vital part of the current graduate program.

Considering my field more broadly, there is little question that those of us bringing feminist approaches to the relatively traditional field of eighteenth-century studies in the 1980s and 90s not only transformed the field but also paved the way for other feminist scholars. When I trained a feminist lens on Swift and Pope (two of the period’s most canonical male writers) in The Poetics of Sexual Myth (1985), I was unprepared for the level of backlash that ensued, but am happy to have danced through that minefield (to borrow a phrase from Annette Kolodny) if my precedent inspired or made it easier for younger scholars to dare to challenge sacred truths (as Kate Millett had done for me).

Please tell us about any recently completed research projects. What current research projects are you pursuing?

I spent the early part of my retirement completing A Cultural History of Women in the Age of Enlightenment, volume 4 of the six-volume Cultural History of Women published by Bloomsbury in 2013 and for which I served as contributing editor.

More recently my research interests have moved away from academic scholarship and toward questions of family history, with a focus on my own family’s multiple immigration narratives (my parents, grandparents and uncles all fled Nazi occupied Europe in the late 1930s, arriving in the U.S in the early 1940s). Sam Dolbear, a young British scholar currently working on the friend network of Walter Benjamin reached out to me a few years ago about my great uncle Max Pollak, who was close to Benjamin when they were both students in Berlin around 1914-16 (in fact, Max’s first wife Dora Kellner eventually left him to marry Benjamin). After a brief imprisonment in Dachau as a political prisoner in the early 30s, Max found sanctuary in Haiti for about a decade before eventually settling in New York. My own father survived the war by joining Max in Haiti in 1939. Ongoing conversations with Sam have uncovered information previously unknown to me, including the fact that Max was taken to Vienna by his mother when he was eleven or twelve years old to see the neurologist Sigmund Freud for a serious case of insomnia. Freud instructed him not to read too much late at night and to stop playing the piano because it was too stimulating. When Max resisted, saying that this would be very difficult because he dearly loved to play, Freud conceded that he should at least limit his time at the piano to only 30 or 40 minutes a day.

What have you most enjoyed having time for in retirement?

Above all, I’ve enjoyed simply having time. (Before retirement, I contemplated a project on “Nothingness;” I now wonder if retirement might in fact be that project….) I spend almost 5 months of the year (much of it along with my husband, Nigel, who is now also officially retired) at our second home in Weathersfield, Vt. where I’ve become an avid gardener and have established about as many large beds of perennials as I can manage. I also grow a few vegetables, most notably garlic, harvesting approximately 80 bulbs a year. To add to these nurturing projects (and with the help of our two daughters, Rachel and Tessa) between 2017 and 2021 we welcomed 4 grandchildren into our lives, the eldest of whom is 5 and two of whom live in nearby Williamston (MI). So life is full and there are lots and lots of distractions.

What are you reading or watching right now and would you recommend it and why? What’s next on your list?

I recently read Ruth Franklin’s award-winning Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life (2016). This masterful biography– which restores Jackson to the literary stature she deserves—has started me reading through her work. I’ve enjoyed Life Among the Savages, Raising Demons, and a smattering of stories, and look forward to all the rest. Jackson lived and wrote in Bennington, Vermont for roughly 2 decades until her death in 1965, so her name still hung over campus like a ghostly presence when I started college there the following year. I studied with her widower, the literary critic Stanley Edgar Hyman (who was on the faculty), but confess (with regret and some shame) that until now I had never read a word by Jackson (well, perhaps I read The Lottery somewhere along the way). How had I (a lover of Swift and Dorothy Parker) missed the often creepy but always rapier sharp satiric wit of this extraordinary writer? Had I been living under a rock? Discovering Jackson in retirement—especially her laugh-out-loud hilarious but also excruciating account of being a “faculty wife”– throws the intellectual culture of my college days (when we read nary a woman in any course that I attended) in an interesting new light and has me pondering the arc of my education and influences — especially the bits left out. I applaud Franklin for bringing Jackson out of the shadows and setting the record straight.

Dr. Tess Tavormina, Emeritus Professor of English

What years did you teach in the English Department?

1978-2012

What are some memorable moments from your English/Film Studies classrooms?

It’s hard to pick out particular moments, though seminar discussions were always something I looked forward to, as well as more occasional creative and interactive class activities like author- and course-concept maps, reader’s theatre adaptations, and so on. Independent studies and honors theses were also very rewarding because of the way they gave students the chance to develop their own topics and approaches (e.g., projects on Tolkien’s runes, or the horse-human bonds discussed in prefaces to Renaissance treatises on horsemanship, or the heroine’s journey as a mythic trope, etc.).

What were your favorite courses and texts to teach and why?

Thematic courses were always fun to design, usually including works from multiple periods linked by some common thread, such as apocalyptic fictions, “world-well-lost” love stories, the epic across time and culture, social health and illness, and so on and on. Understanding both the human differences and commonalities that literature from many places and periods can reveal helps answer the deep questions of meaning that I’ve always thought underpin great literary (and other) art: as Chaucer asks in The Knight’s Tale, “What is this world? what asketh men to have? Now with his love, now in the coldë grave?” Or as a sci-fi writer I once knew used to put it, how does a literary work “ring the great gongs of love and death”?

How do you hope your scholarship and mentoring has impacted your field? What do you hope early career scholars in your field take away from your research?

I’m a big believer in the value of expanding our archive of study, and hope that the work I’ve been engaged in for the last two decades will provide entry points and fresh research materials for other scholars, of whatever career stage, who are interested in the cultural and intellectual histories of the late medieval and early modern periods.

Please tell us about any recently completed research/creative projects. What current projects are you pursuing?

Recent publications:

“Uroscopy in Middle English: A Guide to the Texts and Manuscripts.” Studies in Medieval and Renaissance History. 3d ser., 11 (2014): 1-154.

The Contemporary Middle English Chronicles of the Wars of the Roses. Co-ed. (with Dan Embree). Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell Press, 2019.

The Dome of Uryne: A Reading Edition of Nine Middle English Uroscopies. Early English Text Society o.s. 354. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019. (An edition of several widely distributed Middle English uroscopic/prognostic texts, the most ubiquitous found in over fifty MSS and at least two distinct early prints.)

“A Newly Discovered Veterinary and Medical Manuscript in Early Modern English.” Journal of the Early Book Society 22 (2019): 275-88. (On MSU Libraries MSS 79, A Book of Medicines and Drinks for Horses Bullocks besides Many Other for Other Cattle and Hogs.)

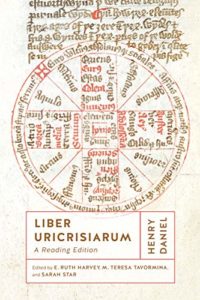

The Liber Uricrisiarum of Henry Daniel: A Reading Edition. Gen. co-editor with E. Ruth Harvey. University of Toronto Press, 2020. (First modern edition based on multiple MSS of an encyclopedic work on diagnosis and other significant medical topics, such as anatomy, embryology, physiology, humoral theory, astro-medicine, etc.; one of the earliest instances of extended ME scientific and medical prose, antedating Chaucer, Trevisa, and other late 14th-c. scientific English writers/compilers/translators.)

“The Heirs of Henry Daniel: The Fifteenth- and Sixteenth-Century Legacy of the Liber Uricrisiarum.” In Henry Daniel and the Rise of Middle English Medical Writing: Contexts, Texts, and Legacy, ed. Sarah Star. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2022. 108-32.

Currently, I’m working on a reading edition of Henry Daniel’s other major work, a massive herbal, also known as the “Aaron Danielis,” again collaborating with faculty and graduate students at the University of Toronto and elsewhere in the ongoing Henry Daniel Project based at UT. COVID has made it harder to get together in person in recent years, but Zoom has been a real blessing for our collaboration across several time zones; I’ve also found it a wonderful way to hear and sometimes interact with many more interesting professional talks than would have been possible in the pre-COVID professional meetings landscape.

What have you most enjoyed having time for in retirement?

It has been very satisfying to have time for the deep archival and research dives required for the various editions I’ve been working on, as well as knowing that bringing these hitherto almost unknown works into modern editions will provide new materials for future scholars and students to explore. It’s also a pleasure to have time for many indoor and outdoor home projects that weren’t possible during the wage-earning years.

What are you reading or watching right now and would you recommend it and why? What’s next on your list?

Loads of public library ebooks and some print books as well, with great appreciation and recommendation of the role played by public libraries in our civic and cultural life. Often these books are simply light mystery and historical fiction or popular science, more mental popcorn than anything else, though now and then I’ll pick up something that takes a bit more attention, whether fiction or memoir or history. I’m more willing to stop reading a given book these days too, if it doesn’t hook me (either for entertainment or for serious interest) by some reasonable point in the reading process. Too many books, too little time, as the sweatshirt says.

Pat O’Donnell, Emeritus Professor of English

What years did you teach in the English Department?

I came to the department in 1997 and retired in 2018; during that time, I served as chairperson from 1997-2007 and from 2012-2014.

What are some memorable moments from your English/Film Studies classrooms?

I think my most memorable moment came in a senior Honors seminar on James, Hitchcock, and Nabokov that I taught a couple of years before I retired. It was (for me) one of those rare and lucky classes where every single student was fully engaged and very enthusiastic; the “chemistry” of the class was such that I simply had to ask an opening question or two, and the group took off from there—I often didn’t have to say another word for eighty minutes! The discovery that teaching could be about listening and silence came as a revelation, and one I wish I had come upon much earlier.

What were your favorite courses and texts to teach and why?

I always liked teaching the 210, 211 and 280 courses along with Bennett and Royle’s terrific Introduction to Literature, Criticism and Theory partly because of the diverse range of students one encounters in those courses and also because the sense of discovery, for some of them, was so strong. I enjoyed teaching the senior honors seminars, and I also liked teaching graduate courses in theory of the novel and modern/contemporary literature, especially those two or three courses I had the opportunity to teach collaboratively with Scott Juengel and Justus Nieland. I fondly recall the terrific conversations we had during those courses.

How do you think your scholarship and mentoring has impacted your field?

I think the places where any impact I may have had are in my editorial work and in my role as a department chair. In the former arena, I have greatly enjoyed bringing new work and younger scholars to the fore as editor of Modern Fiction Studies and two large literary encyclopedias I have edited that have involved collaboration with co-editors and the opportunity to recruit an international cast of scholars to participate in building a large-scale reference work. If Academia is anything to go by (taken with the prescribed grains of salt) the work under my name that is most often cited is Intertextuality and Contemporary American Fiction, which I co-edited with Robert Con Davis-Undiano many years ago—this bears out my theory that the collaborative, editorial work has had the most impact. And as department chair, I found that the most enjoyable and rewarding aspects of the job was recruiting new faculty, getting to know their work, and seeing faculty through the promotion/tenure process.

What do you hope early career scholars in your field take away from your research?

I have always valued close reading and the careful integration of theoretical and critical perspectives into the act of reading in my work. I know there are many other valuable approaches and methodologies, but my hope is that anyone reading my own work would gain from it a deepened sense of what close engagement with the words and language on the page, or the image on the screen, can bring about in terms of enlightenment, contextual awareness and satisfaction.

Please tell us about your recently completed research projects. What current research projects are you pursuing?

Last year, I had a single-author book on Henry James and contemporary cinema published, and this year, a two volume encyclopedia of contemporary American fiction of the last forty years that involved two co-editors and about 250 contributors. This left me a bit exhausted and, frankly, at sea in regards to taking on major new projects. But in the middle distance I am contemplating a book on the noir novel, The Postman Always Rings Twice, and the numerous film adaptations of the novel from the first (Le Dernier Tournant) in 1939 to more recent ones such as U-Wei Haji Saari’s Buai-laju-laju in 2004 Christopher Petzold’s Jerichow in 2008. I’m interested in the genetic code of the novel and how it moves through seven films coming from six different countries over a period of roughly 70 years and as they reflex myriad shifting aesthetic, political, national and cultural contexts during that time.

What have you most enjoyed having time for in retirement?

Above all, the time to read, and to annotate my own reading in ways that I have not been able to do as intensively since I was in graduate school. I am working my way through ridiculously long reading lists of the eighteenth century novel, Victorian fiction, and big, long, complicated contemporary novels which I will never finish (the lists, that is) in this lifetime, or several others for that matter. My wife, Diane, and I also enjoy traveling, which we are planning to do more often in the next few years than in the last few, for obvious reasons. Both of us are enjoying the opportunity to explore the great states of Washington and Oregon, and the city of Vancouver (WA, not BC), where we moved shortly after I retired. We both grew up in the West—more specifically, the suburbs of Arcadia and Corona outside Los Angeles—and I did all of my gradate work in northern California, so we’re very happy to be back on the West Coast and in the Pacific Northwest after peripatetic academic careers spent in Arizona, West Virginia, Germany, Indiana, and Michigan (the last, our longest stay, in East Lansing for twenty-one years). We live a couple of miles north of the Columbia River with Mount Hood in view on clear days, and downtown Portland within 20 minutes outside rush hour. And last but certainly not least, we are enjoying being in the same neighborhood and spending time with my daughter, Sara, son-in-law, Ed, and amazingly energetic granddaughter, Luna, now four and rapidly becoming five.

What are you reading or watching right now and would you recommend it and why? What’s next on your list?

My Victorian novel of the moment is Wilkie Collins’ No Name, which combines the sentimental, the strange, the legalistic, and the mysterious in typical Collins fashion. I recently finished re-reading Evan Dara’s The Easy Chain which I can recommend if you are up for a dense, long, experimental meta-novel; before that, Philip Hensher’s The Northern Clemency, a big, multi-generational novel about suburban and working-class families in Yorkshire struggling against the advent and aftermath of Thatcherism as it proceeded from the ‘70s to the ‘90s in Britain. For something of a busman’s holiday, I am also currently reading Susan Choi’s A Person of Interest, an “academic” novel (kind of, but not really) that Scott Juengel recommended to me; if a job in the academy has ever seemed to you, as it has to me, beset by paranoia, then this is a must-read. My other reading project, sporadically attended to, involves reading Henry James’s short stories, in chronological order, alongside Chekov’s short stories, in chronological order, alternating story by story between the two. I plan to tackle that a bit more vigorously in the coming weeks.

Dr. Pat O’Donnell, Emeritus Professor of English

What years did you teach in the English Department?

I came to the department in 1997 and retired in 2018; during that time, I served as chairperson from 1997-2007 and from 2012-2014.

What are some memorable moments from your English/Film Studies classrooms?

I think my most memorable moment came in a senior Honors seminar on James, Hitchcock, and Nabokov that I taught a couple of years before I retired. It was (for me) one of those rare and lucky classes where every single student was fully engaged and very enthusiastic; the “chemistry” of the class was such that I simply had to ask an opening question or two, and the group took off from there—I often didn’t have to say another word for eighty minutes! The discovery that teaching could be about listening and silence came as a revelation, and one I wish I had come upon much earlier.

What were your favorite courses and texts to teach and why?

I always liked teaching the 210, 211 and 280 courses along with Bennett and Royle’s terrific Introduction to Literature, Criticism and Theory partly because of the diverse range of students one encounters in those courses and also because the sense of discovery, for some of them, was so strong. I enjoyed teaching the senior honors seminars, and I also liked teaching graduate courses in theory of the novel and modern/contemporary literature, especially those two or three courses I had the opportunity to teach collaboratively with Scott Juengel and Justus Nieland. I fondly recall the terrific conversations we had during those courses.

How do you think your scholarship and mentoring has impacted your field?

I think the places where any impact I may have had are in my editorial work and in my role as a department chair. In the former arena, I have greatly enjoyed bringing new work and younger scholars to the fore as editor of Modern Fiction Studies and two large literary encyclopedias I have edited that have involved collaboration with co-editors and the opportunity to recruit an international cast of scholars to participate in building a large-scale reference work. If Academia is anything to go by (taken with the prescribed grains of salt) the work under my name that is most often cited is Intertextuality and Contemporary American Fiction, which I co-edited with Robert Con Davis-Undiano many years ago—this bears out my theory that the collaborative, editorial work has had the most impact. And as department chair, I found that the most enjoyable and rewarding aspects of the job was recruiting new faculty, getting to know their work, and seeing faculty through the promotion/tenure process.

What do you hope early career scholars in your field take away from your research?

I have always valued close reading and the careful integration of theoretical and critical perspectives into the act of reading in my work. I know there are many other valuable approaches and methodologies, but my hope is that anyone reading my own work would gain from it a deepened sense of what close engagement with the words and language on the page, or the image on the screen, can bring about in terms of enlightenment, contextual awareness and satisfaction.

Please tell us about your recently completed research projects. What current research projects are you pursuing?

Last year, I had a single-author book on Henry James and contemporary cinema published, and this year, a two volume encyclopedia of contemporary American fiction of the last forty years that involved two co-editors and about 250 contributors. This left me a bit exhausted and, frankly, at sea in regards to taking on major new projects. But in the middle distance I am contemplating a book on the noir novel, The Postman Always Rings Twice, and the numerous film adaptations of the novel from the first (Le Dernier Tournant) in 1939 to more recent ones such as U-Wei Haji Saari’s Buai-laju-laju in 2004 Christopher Petzold’s Jerichow in 2008. I’m interested in the genetic code of the novel and how it moves through seven films coming from six different countries over a period of roughly 70 years and as they reflex myriad shifting aesthetic, political, national and cultural contexts during that time.

What have you most enjoyed having time for in retirement?

Above all, the time to read, and to annotate my own reading in ways that I have not been able to do as intensively since I was in graduate school. I am working my way through ridiculously long reading lists of the eighteenth century novel, Victorian fiction, and big, long, complicated contemporary novels which I will never finish (the lists, that is) in this lifetime, or several others for that matter. My wife, Diane, and I also enjoy traveling, which we are planning to do more often in the next few years than in the last few, for obvious reasons. Both of us are enjoying the opportunity to explore the great states of Washington and Oregon, and the city of Vancouver (WA, not BC), where we moved shortly after I retired. We both grew up in the West—more specifically, the suburbs of Arcadia and Corona outside Los Angeles—and I did all of my gradate work in northern California, so we’re very happy to be back on the West Coast and in the Pacific Northwest after peripatetic academic careers spent in Arizona, West Virginia, Germany, Indiana, and Michigan (the last, our longest stay, in East Lansing for twenty-one years). We live a couple of miles north of the Columbia River with Mount Hood in view on clear days, and downtown Portland within 20 minutes outside rush hour. And last but certainly not least, we are enjoying being in the same neighborhood and spending time with my daughter, Sara, son-in-law, Ed, and amazingly energetic granddaughter, Luna, now four and rapidly becoming five.

What are you reading or watching right now and would you recommend it and why? What’s next on your list?

My Victorian novel of the moment is Wilkie Collins’ No Name, which combines the sentimental, the strange, the legalistic, and the mysterious in typical Collins fashion. I recently finished re-reading Evan Dara’s The Easy Chain which I can recommend if you are up for a dense, long, experimental meta-novel; before that, Philip Hensher’s The Northern Clemency, a big, multi-generational novel about suburban and working-class families in Yorkshire struggling against the advent and aftermath of Thatcherism as it proceeded from the ‘70s to the ‘90s in Britain. For something of a busman’s holiday, I am also currently reading Susan Choi’s A Person of Interest, an “academic” novel (kind of, but not really) that Scott Juengel recommended to me; if a job in the academy has ever seemed to you, as it has to me, beset by paranoia, then this is a must-read. My other reading project, sporadically attended to, involves reading Henry James’s short stories, in chronological order, alongside Chekov’s short stories, in chronological order, alternating story by story between the two. I plan to tackle that a bit more vigorously in the coming weeks.

Dr. Ken Harrow, Emeritus Professor of English

What years did you teach in the English Department?

It wasn’t a clear beginning. I was originally in the Humanities Dept. (came in 1966), and somewhere in the 1980s I offered to teach a course in African literature in the English Dept. Before then there was nothing in African literature. They gave me the course, and that was the start of my link. Before that I had taught an African Humanities course for some years. By 1987 I moved over to English, incurring the anger of my former chair who felt, correctly, that MSU was about to abolish the Humanities Dept. When it did, a number of faculty joined English, like James Seaton, Bill Vincent, Don Gochberg, Surjit Dulai, and myself. I was officially in English in 1987. I stayed until retirement in 2018.

What are some memorable moments from your English/Film Studies classrooms?

I once taught a film that was not well-received by the class. Not sure which one it was. A difficult film. By the end of the class discussion, the students seem to have changed from their original impression, and found value in it. I remember once trying to deal with students’ expectation that U.S. policies toward the Third World involved generous giving. In the end, teaching about U.S. imperialist policies met students’ opposition, and the films and novels I taught countered their preconceptions about American generosity, etc., over and over. Jamaica Kincaid or Walcott or Achebe or Ngugi presented them with alternative views of the world. More nuanced was Coetzee, Gordimer, Wicomb and the complex history of Apartheid. Mostly I taught sub-Saharan literature that emphasized Black culture and history, not so much that of white South Africa. But the first course that really opened them to the politics of the Third World was called Third World literature and later Third World Cinema, and it included films from Latin America, Africa, Asia, and the Middle East. After a while the lessons became historicized, older, and came to represent times past for the students. The most exciting moment in The Hour of the Furnaces comes at the end with the repetitive beat and close up of Che’s face in his coffin. It was overwhelming. But by the time I taught that class in subsequent years, the students didn’t know who Che Guevara was.(some told me they recognized his face from T-shirts, but didn’t know who he was). That was memorable. Another was introducing African American Cinema to the Dept., to MSU, and setting up a series of amazing courses with visitors on Malcolm X. One such evening brought Malcolm’s brother from here in Lansing, along with a speaker from NYC. I ran the course with Ngere, a Lansing activist. It was exciting to have our academics meeting his activism. Another involved the presence of Gerima who presented Sankofa to our campus. Another was having the ALA conference here, bringing Djibril Diop and a dozen other great filmmakers. The African film courses were exciting those days with many students enrolling, and some now teaching. More recently, I taught 9 Muses by Akomfrah in London. He was supposed to be there to present the film, but missed his train. We saw it and discussed it anyway, and the next day he showed up. Had he been there the first day, the students would have been largely baffled, and would have contributed little. But after the discussion the previous day, they were primed, and Akomfrah was brilliant—and so were the students.

What were your favorite courses and texts to teach and why?

I loved both literature and film courses dealing with “Third World” literatures and film, including Third Cinema. They really gave me openings onto films from everywhere from the Philippines to Egypt to Chile to Argentina, Brazil, Tunisia and Morocco, and of course my sub-Saharan films. The excitement of teaching from around the world—that is, the “Third World,”– and finding a politics of engagement that took on neocolonialism and later postcolonialism–became the core of my work in Africa. I moved from teaching African literature to African cinema, and as I was teaching, researching and writing about both areas, I found myself in the luckiest position of all. I loved the more challenging work, like Trin T. Minh-ha’s writings and films, especially Reassemblage. I loved Djebar and Ben Jelloun, but most of all, teaching African and postcolonial thought, literature and films to graduate students. As a number of them pushed me with Bhabha and Spivak, I felt enriched. I taught a French feminist course, helped by the advice of Ellen McCallum, which led to a book on feminism and African women’s literature. I co-taught postcolonial courses with Salah Hassan, and he and the grad students made the encounters compelling. He was my most important collaborator in trying to reshape our field here at MSU, in teaching, coursework, course development, conferenes—in a million ways. Before that, the great excitement came in the period when Spivak and Bhabha, and Said, were reshaping our fields, and our courses focused on their work. All three were invited at some point and came to our campus, at invitations of which our dept was the sponsor (again Salah Hassan was key to our bringing Spivak, and making the event happen). They were charged moments: Said with many other major theorists, like Gates and Appiah, etc., for the African Literature Association conference. Spivak right at the moment of the afterwash of 9/11; Bhabha with Pat O’Donnell improvising questions after his talk (which I was still trying to digest!). Many others as well, but the main thing was the feeling that we had a cohort of postcolonial people in our dept who were actively shaping the program, and we made events and speakers and courses seem vital. That shifted naturally over time, and eventually I looked more and more to film to generate that excitement. I remember well first teaching Bhabha to a grad class that included Carmela Garritano and her mates; it was electrifying. I remember teaching Lacan and French feminists, with considerable excitement, especially Irigaray and Cixous. Lately, reaching out to Thai cowboy films, to Weerasethakul or Claire Denis or Wong Kar Wai made great sense, as we were stretching our corpus of films across the world. I loved teaching genre in my last few years. But the heart of it remained African and African diaspora, including Caribbean works—originally literary, eventually also films. And I found the larger reach of Black cinema in every sense essential to my interests. Lastly, I would not have been able to enter into the world of teaching cinema without Bill Vincent, who was integral to its introduction on campus, and our department. One of many exciting moments came when he invited Kureishi here. And we taught film In Britain overseas for many years, thanks to his innovations. Other great figures who came to MSU during my years here included Bekolo, Akomfrah, Mambety, Gerima, and many other Black filmmakers. In later years, Safo was invited by Carmela Garritano, another exciting event. Many of the students were taught collaboratively, with dissertations co-directed with Jyotsna Singh and Salah Hassan. Jyotsna brought many wonderful students to our department, and was crucial to expanding postcolonial studies. And Pat O’Donnell went a long way in helping with that expansion, as did Steve Arch as well. I really believe our department was one of the most exciting places to study postcolonial work thanks to these colleagues. As film studies became formalized in our department, I was given the chance to teach a wide range of film courses, and the film studies faculty became absolutely my most wonderful and appreciated colleagues.

How do you hope your scholarship and mentoring has impacted your field? What do you hope early career scholars in your field take away from your research?

“Hope” is the right word. Mostly I feel that what I taught or published would have gone out like some kind of food for people/fish to nibble on in the ocean. Not to hook them, but to hook their attention and maybe inspire thoughts or reactions. When we had conversations in conferences and references to my works would arise, it felt good, but temporary. More important and long lasting were comments, even debates and refutations, in publications or conferences. From the very earliest days I felt it important to help bring attention to major theorists like Said and Gates and Appiah, Trin T Minh Ha, Irele, Mudimbe, and many others whose structuralist and then poststructuralist theorizing was often ignored or discounted in our field, I believe because it was regarded as too Western, or not as grounded in African culture. Eventually, no one could ignore them, and great writers like Mudimbe, Gikandi and Mbembe, succeeded in reshaping the field. I was part of that wave of people determined to bring those thinkers into our work, and to some extent that happened. The place most central to the change remained the African Literature Association conference, along with a few others. We were marginal to the Comp, Lit or MLA conferences, and I stopped attending them. The SCMS conference also ignored Black cinema, by and large. It was maddening.

In the early years—the 19070s and 1980s, the prevailing focus on sociological readings was limiting the ways of analyzing novels; it took work to go beyond literalist readings of texts. Achebe wasn’t important because he embodied and reiterated Igbo proverbs, but because he could put words and images together in new and exciting ways. Eventually magic realists like Sony Labou Tansi were recognized, and in the Caribbean Chamoiseau embodied that turn as well, as did Glissant in the years after Creolité had become dominant (that coming after Negritude’s dominance). But things continued to change. We are in a world where Bhabha’s hybridity has prevailed, and now passed; and new postcolonial notions, especially grounded in material culture, have their new stars, like Adichie, Cole, NoViolet Bulawayo,or Helon Habila. Afrofuturism and afropolitanism with Selasi, have gradually taken the new dominant position. I see the new generation of filmmakers as extremely, at times excessively, influenced by western creative writing programs. I am not always thrilled when I see western cinema trends, and their schools, have begun to train African filmmakers in following commercial algorithms, such as Netflix would want–dominating in a world of global commercial and neoliberal values. The small presses or independent films are lost in competition with global publishers or airline screenings. But despite this, great filmmaking still continues, and more and more across the continent. I am still working to publish works on African cinema, literature, and culture, in the series i edit with MSU Press, work I’ve done for perhaps ten-twelve years now. I’ve seen Cajetan Iheka’s career take off as ecocriticism has become mainstreamed, in no small measure due to his work which began with his dissertation here at MSU. Material culture figures a lot in Carmela Garritano’s projects and in Olabode Ibironke’s projects, which also now include Nigerian popular culture. The dissertations of these former MSU graduate students were vital. Same to be said of Connor Ryan’s dissertation on Nollywood, now having morphed into a book to come out shortly with UMich press. What did I want them to take away? Simply that the work we did, each in our own way, took as vital the creative texts, films, thought of African writers and filmmakers. That it mattered enormously, and that we could participate in making that field critical. The careers of these students came to matter more to me than my own—as mine began to reach its end, I saw with great happiness more and more of my students with good jobs and careers developing.

Please tell us about your recently completed research projects. What current research projects are you pursuing?

After working for a number of years on the question of how African cinema accords with, or discords with, global cinema, or world cinema, covid struck and I was stuck at home for three years. In that time I read continually texts dealing with the physics of cosmology and quantum, and relativity. I wondered how the notions of space and time that were radically reshaped in the early twentieth century, especially beginning with Einstein’s annus mirabilis 1905 when he published foundational papers on special relativity, could be used to ask questions about space and time in African cinema. Really, I wondered how space and time in cinema, all cinema, might be re-conceptualized using the physics notions of space and time, as understood today. Almost no one had raised this issue: maybe, a bit in Deleuze, but he abandoned it. I read a lot, and major physicists like Greene, Thorne, Sean Carroll, Karen Barad and Carlo Rovelli, and many more, led me to appreciate not only central questions about these approaches, but their differences in views. Time became and remains my favorite topic by far. I wrote essays on key films, almost all African; got deeply into the work of Kentridge, and others including Kiarostami (ABC Africa and 24 Frames) and Marker (Sans Soleil) whose African films intrigued me; and focused the rest on African filmmakers, always seeking to use notions of relativity and quantum mechanics to query space and time. Space and Time in African Cinema and Cine-Scapes came out with Routledge a couple of months ago. Since then I’ve returned to, and finished another manuscript on African film and world cinema, and hope to have Routledge accept it soon. The underlying argument there is to see how African films from the 1990s on to today have shifted under the impress of digital and global pressures, and resisted the horrible labels of World Cinema or similar neoliberal tendencies. When I am done with preparing that ms. for publication, I will return to readings on time, the most astonishing topic imaginable. And when I look for examples of where to think about analyzing texts, it will almost certainly be predominantly in African cinema, where amazing work is being done every year.

What have you most enjoyed having time for in retirement?

I enjoyed having days in which I could read or watch films and write, without feeling the pressure of meeting deadlines or having to prepare for meetings or courses. Getting to know the work of colleagues in the dept or the profession was always enriching, sometimes greatly inspiring, for which I am eternally grateful I was so lucky to have the colleagues I had for the last ten years or so of my career. And that came with the grad students who always made the work seem joyfully important. I am now trying to take on promotion recommendations or book reviews only when I think I owe it to the author or professor—owe it to the profession. I shy away from those I can, reserving my time for the work above that I mentioned. I now have 6 grandchildren, and 4 are little ones. Liz and I spend a fair amount of time with them—in Cambridge or, until this year, in Chicago. Retirement has gone far in enabling us to take off for 2-4 weeks to be with them. But to get to the question, not having to produce scholarship or teach courses meant I could pick up a book by Stephen Hawkings, read as much as I could in a field distant from my own specialization, and then ask, how can we bring these fields into dialogue with each other, without worrying if my salary or standing in the department or college would be affected. I took my first sabbatical in 1973-74 in France and North Africa, to study Camus and Maghrebian literature. When I returned, I had decided to drop Camus and remain focused on Maghrebian authors. I was up for tenure and promotion that year; and the dean of the college, an old-school thinker, told me to drop the North African dilettantism and stay with the European authors who had been important to my dissertation work. I ignored his advice. In 1977 Liz and I went to Cameroon, on a Fulbright. I stayed two years, and came back devoted to the study of African literature, to everything African, and to the African diaspora in the Caribbean. I was lucky. I was lucky MSU, and especially the English Department, supported me in that serendipitous choice. Lucky to have colleagues who rewarded me for that work, and students who came to take courses in African literature and then cinema, and later in postcolonial studies. Lucky that that dean left and new people in English saw worth in these fields. Lucky indeed. And grateful.

What are you reading or watching right now and would you recommend it and why? What’s next on your list?

I just finished a difficult novel by Sarr who won the Prix Goncourt for La plus secrete memoire des hommes, and am halfway through the weird novel Soumission by Houellebecq. Two worlds apart: a Senegalese grand prize winner who brings out the nuances of French colonial mentalities and history, and this anti-Muslim speculative writer from Reunion who appears on another cutting edge of fiction, redefining how we think about rightwing politics in a really creepy fashion. There is one issue today, immigration, that shapes everything that is central to the political pulse in Europe and now Africa.

Mostly I am focused on films. I continue to love the older school that came from Black British Cultural studies, folks like Hall and his film-biographer, Akomfrah. But more important to me are the Africans’ work, like This Is Not a Burial, It is a Resurrection by Lemohang Mosese, from Lesotho of all places, that I loved. I loved the Sudanese film, Talking About Trees by Ibrahim Shaddad, and more recently all the films by Rosine Mbakam, especially Prism, which you can get through Icarus Films. I enjoyed Airconditioner by Fradique, and have come to appreciate now films from across the continent. I love the courageous work of Kenyan filmmakers like Rafiki by Wanuri Kahiu who is challenging the government with its lesbian message and characters. She is setting a trend. Another example was Mignonnes, by Maimouna Doucoure, and other young women filmmakers. I love Mati Diop’s recent films, including Mille Soleils and her great success with Atlantics, a zombie movie. I liked Dyana Gaye’s Des Etoiles, showing us more and more the work of young women from across the continent. Another is Marwa Zein, with her Khartoum Offisde. These are all redefining the roles of women in making African films. But what I will be focusing on in my future work will certainly be how to think about time. The multiverse example of Everywhere, Everything, All at Once matters to me not just because it is at an angle to the Netflix algorithm or the mall movie studio films, but because, popular or not, it is replacing the Arrow of Time with another paradigm. This is how Michelle Wright would have Black Thought challenge the conventional classic thought and science from Newton’s day on, with the uncertainties that won’t be disentangled soon. I know Ellen McCallum is equally taken by the ways Barad opened this challenge for feminist thinking and physics. Now it is time I hope to play with. A great place to start is with the articles of Quanta Magazine. You don’t really know how to solve the equations to get the ideas, and I will be following their articles regularly.

Dr.  Ned Watts, Emeritus Professor of English

Ned Watts, Emeritus Professor of English

What years did you teach in the English Department?

I taught in English between 2004-2020. Prior to that, from 1993-2004 I taught in the Department of American Thought and Language (ATL) / Writing, Rhetoric, and American Cultures (WRAC).

What are some memorable moments from your English classroom?

Introducing students to texts from places and peoples wholly unfamiliar to their experience: Indigenous Americans, Australians (white and Indigenous), even Michiganians. Students approached these with no preconceived notions or contexts, and so read, listened, and responded with an energetic freshness. After a few weeks, students were responsible for initial presentations of texts/authors/subjects, starting the conversations. What they found necessary to discuss often differed from what I had in mind, and those were the best sessions.

What were your favorite English courses and texts to teach and why?

For classes, Michigan Literature, American Indian Literature, and Australian literature. I always enjoyed IAH 207: “Michigan: The Life and Times of Where You Are.” At the graduate level, I enjoyed “Race and Early American Literature” and “Whitman and his Followers.”

A text I found myself returning to in many courses was Andrew Blackbird’s (Odawa) History of the Ottawa and Chippewa Indians of Michigan People (1887). It’s brief and available online for free, though I understand MSU Press is developing an edition. Blackbird blends tribal, racial, and family history with legend, polemic, and anecdote. Intertribal, intratribal, interracial conflicts are all addressed—an amazing account of the complexity of indigenous experience in the nineteenth-century. He ends with two seemingly contradictory chapters: one urging his fellow Odawa to accept white education and occupations in the Dawes Act, and one urging them to cling to their culture and language, followed by twenty pages introducing their language to white readers. Students always engaged and wrote well about Blackbird. My own reading is in an essay about Blackbird and other 19th-century Anishnabeg intellectuals in The Sower and the Seer (2021).

How do you hope your scholarship has impacted your field? What do you hope early career scholars in your field take away from your research?

I was one of the first scholars to apply what is now called Settler Colonial Studies to early American studies in my first book, Writing and Postcolonialism in the Early Republic (1998) and the collection I co-edited with Malini Johar Schueller, Messy Beginnings: Postcoloniality and Early American Studies (2002). The Intro to the latter still gets abut fifteen citations a year. Most of my later book projects were informed by delving into the anxieties in American culture based in its settler identity. Though the taxonomy has shifted over the years, I hope younger scholars can continue to place American writing in a global context by continuing to reframe its complexity in the evolving theoretical frameworks I helped to initiate.

Have you completed any research projects while in retirement? If so, please tell us about them! What current research projects are you pursuing?

Work on the most recent book with my name on it—Cannel Coal Oil Days: A Novel by Theophile Maher (2021)—was completed just as lockdown and retirement began, though copyediting and proofing carried over into Fall 2020. Maher was my great-great-grandfather, a Sorbonne-educated chemical engineer, who wrote a semi-autobiographical novel about managing, reforming, and running a coal oil plant upstream from what is now Charleston, West Virginia, as the Civil War approached. As it did, he worked with both white Appalachians and local enslaved families to organize abolitionist efforts and encouraging the secession of a free West Virginia from a slave-holding Virginia. As a mining engineer, his protagonist works to preserve water resources and to reduce toxins leftover from oil production. I edited the manuscript from 390 handwritten pages on stenopads from 1887 through blind peer review and production by West Virginia University Press. More recently, I’ve been doing a lot of manuscript and book reviewing and still serve on the editorial board for Early American Literature, the leading journal in my field.

My current book project—tentatively, The Indian Hater in American Life, Legend, and Literature, 1760-1860—was started in 2006, but was shelved as I took up Colonizing the Past (2020) and other projects (like being Undergrad Director!). Earlier this year, I returned to it and am about one third done. It addresses textual representations of a very specific historical phenomenon: white men who vowed and initiated racial vengeance against ALL indigenes for familial deaths resulting from settler invasions of frontier spaces. The upper-case H distinguishes them from ordinary racists. Over seventy versions of the story exist. Authors who addressed it range from Benjamin Franklin to Herman Melville. Themes of toxic masculinity, PTSD, hate crimes, the gothic, and atavism interact with my usual interests in settler nationalism and frontier indeterminacy.

What do you look forward to having time for in retirement?

More time for family and friends. Now that my older son (severely disabled) has been graduated from educational services and lives in a group home, I spend about three days a week with him. I’ve also been able to spend time on the family land in Allegan County and to re-cultivate many old friendships there from before my career really began.

What are you reading right now and would you recommend it and why? What’s next on your list?

I alternate between recreational and “serious” texts. Recreationally, I’ve been reading two things: first, series in sequence. Normally, you read these as they come out, once a year, but reading all of them at once reveals a secondary narrative and continuity. For Michigan writers, Loren Estleman’s Detroit mysteries or Bryan Gruley’s Starvation Lake and Bleak Harbor series, or, even more locally, Stephen Mack Jones’s August Snow books. Also medieval historical fiction: Sharon Penman’s series on the Angevin Empire and Ken Follett’s Kingsbridge series. As to more literary texts, Robert Jones Jr.’s The Prophets was the best book of 2021 that I’ve read. As an early Americanist, I cannot recommend it enough. Intersections of race, history, queerness, memory.